No matter the eventual drama or even the final score, this year’s Oppo Malaysia Cup Final between Pahang and Johor Darul Ta’zim was a magnificent spectacle off the pitch. Two teams with massive and passionate travelling support made the Final an occasion to remember even before a ball had been kicked.

That the players then made it one of the great sporting occasions with a 2-2 draw before Pahang won the penalty shoot-out was an extra double-topped bonus. Millions watched the drama unfold on TV. Estimates put the total audience on Astro Arena and free-to-air at close to 6 million viewers.

Now, if the final had been PDRM against Felda – as was a real possibility at the quarter final stages – the audience, I would argue, would have been less than one fifth of that. And there’s a reason for that. And it’s a reason that seems not to be taken on board by many responsible for football throughout South East Asia.

Pahang and Johor Darul Ta’zim both represent a geographical location. To their fans, they are something to closely identify with because Pahang and JDT are relevant to their lives. The final was a sporting event relevant enough for one in 5 of the country to stop and watch. That means that the names of Pahang and Johor matter beyond the confines of the supporters of the teams.

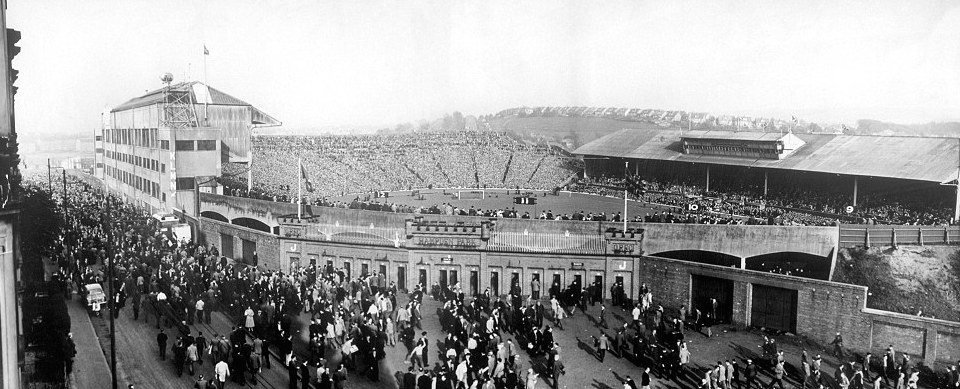

Same thing in the AFC Champions League final where the supporters of Western Sydney Wanderers made the home leg of the tie seem like an extension of a raucous family party, and then celebrated long into the night when their team – THEIR team – held off Al Hilal in the second leg to become the first Australian team to win the AFC Champions league.

The celebrations in Western Sydney – and the Parramatta township in particular – made a statement that a game of football really mattered to a community. More than 5,000 turned up in central Parramatta to cheer on their team as they played in Riyadh against Al Hilal. Western Sydney’s success has come very quickly, as has their importance to the community. The club is only three years old. A note here that Western Sydney are called Western Sydney because they play their games in ? …. Western Sydney.

And the same in Buriram, Thailand, where another fairly recent club saw that it were to succeed, it needed to be built on developing a community feel first. On the pitch, Buriram wangled their way into the Thai Premier league by taking over and re-locating PEA. Since doing so, they have achieved outstanding success, and passionate support. Success at home and in the AFC Champions League has brought the small town of Buriram to International prominence.

But its biggest success is that it is based on being a club central to the community. Go to Buriram and you will see a smart, football facility built with audience in mind, and a town buzzing with expectation whenever match-day arrives. Now imagine if they remained “PEA”. Who would be interested in PEA? Where is PEA? Who do they represent?

Indeed, look at any great team in world football and, virtually without exception, they grew from a community. They represented a community. They played in a community and they developed a strong local fan base. From that base, they were able to develop, sometimes, on a global scale, and subsequently market themselves and make money. But always, always, always they had a stable community base from which to grow. There was a tangible people centred reason for their existence.

Real Madrid, when they started, represented a section of the Madrid population and grew to the behemoth they have become with Central State help. But their roots were community and local. Atletico Madrid represented a different section of Madrid. Barcelona developed in Spain as a focal point of Nationalism for Catalonia. Espanyol were the more pro-Spanish and wealthy element. Again, there was a core community that the teams represented. These rivalries have been built and nurtured over the decades. And while the community element is the base, there is also the fact that fixtures between the teams have been recorded either in terms of data or film, or even word-of-mouth.

Look at England. Liverpool are based in, and come from, Liverpool. Burnley are called Burnley because they play in Burnley. Manchester City and United play close enough to Manchester for them to reasonably take the name. Fans born in Wolverhampton wouldn’t dream of supporting any team other than the once-mighty Gold and Black Wolves.

Lower down the football league pyramid and guess where Bury play their football. Bury? Correct. Southport? Southport. Or Bridlington? Or Colwyn Bay? And all represent the towns and communities whose name they take, and are involved in community work. All have age teams playing in local leagues.

Capital city clubs tend to have less specific geographical references to them, but each absolutely represents their region. Of London’s many clubs, Queens Park Rangers are West London, West Ham are East London, Crystal Palace represent the South, Tottenham Hotspur the North, with Chelsea and Fulham the more central area. It is known generally whom they represent and the bulk of their support in the start up days comes from those communities.

Even in the former Eastern bloc during Communist times, the football represented the people in their battles against “big, bad Moscow”. Kiev, Tbilisi, Vladivostok, Ararat Erevan et al all used football as a method to illustrate regional pride. These weren’t marketing gambits; they were a community using a football team as a form of regional identity.

In Asia, and elsewhere, it has constantly amazed me – even with so many positive examples of what you need to make football work – that so many football teams are created without any kind of real community base. Here in Malaysia, there are numerous examples.

For the Oppo Malaysia Cup Final there was a real chance that we may have had a match-up between PDRM and Felda United. Whilst both have assembled good teams and been allocated generous budgets to do so, don’t both Felda and PDRM completely miss the point of football? If you can answer the question, “where is Felda?” or “where is PDRM?” then you are one up on me. Neither even has their own home field. PDRM played at Selayang, Shah Alam and Paroi in the Malaysia Cup alone. Felda played at Shah Alam, Selayang and Temerloh in the Malaysia Cup. Huh?

My “favourite” of all time is KL Plus? They reached the top division in Malaysia a few years ago. But ask the question – as did the writer of the excellent JakartaCasual.blogspot.com, Anthony Sutton – who, in their right mind, could choose to support an expressway?

It’s understandable to form an amateur team for company employees and trying to play as at high a level as possible. But who would honestly have a real reason to support a company team?

Sime Darby. There’s no doubt that they have developed into a nice team but: Where are they based? Who do they represent? What community do they represent? Why would you support them unless you worked for them? Are there ever going to be thousands who support them? So why – other than pure marketing purposes – do they exist as a football team. What longevity do they have?

T-Team – a creation that may or may not survive dependent on the politics of the time. Certainly if there is a community they represent, I couldn’t tell you who it is. Terengganu State already have a representative. And if it’s a marketing strategy, what is it marketing? Unless you already knew what the “T” stands for, how would you know? Why not simply call themselves Kuala Terengganu? At least it gives some geographical belonging.

Singapore’s S-League has long taxed my understanding. The League itself is invariably competitive. This season, as so often over the last decade, it went down to the last game of the season before Warriors won the title. And yet it continually struggles for fans and recognition and for 2015, three of its more community minded teams will disappear.

I would argue – and did in an interview I had as an outside candidate for the CEO post of the S-League not long ago – that there is a lack of any community identity with the vast majority of clubs and that they were never set up to truly represent a community, and hence their dislocation from any form of loyal fan-base is almost inevitable.

Case in point. Who are “Warriors”? Who do they represent? What community is supporting them? This isn’t a criticism of the players or even the League which remains ultra competitive. Warriors is at least better that SAFFC! Try telling someone you support SAFFC and watch their eyes glaze over.

The quality of the League is quite respectable. Very respectable. The competitiveness of the league is not in doubt, and yet very few see or saw football as a way to bind a community.

Tampines Rovers and Woodlands Wellington were two of the best examples of a club that represented a community. That was until Tampines’ stadium was taken from them for upgrading and so they moved to the other side of the island to play at Clementi? Huh?

The problem for Tampines is that they didn’t and don’t own their own base so were merely renters of a stadium that, in a completely separate discussion, is not suitable for spectators to watch football at. Tampines were not ever in a position to be genuine contributors to community spirit.

To digress, in England, when Wimbledon moved their home to Milton Keynes, there was widespread outcry that a club could be uprooted from its own community. More than a decade on, there is still animosity. From the “old” Wimbledon, taken over by Milton Keynes, a new AFC Wimbledon grew. The club mattered to their community. When Tampines moved to the other side of the island of Singapore, there was barely a murmur.

Woodlands remained true to themselves and played in Woodlands. “Played” is important – past tense – because they will be sitting out the 2015 season having formed an alliance with Hougang for 2015. Again, if I am living in Woodlands, why would I even think of taking the MRT to Hougang to watch a team that doesn’t represent me?

Geylang rent a stadium in Bedok. Tanjong Pagar are another team who will sit out the 2015 season as operating a fully professional club becomes too expensive. Even when they played, whom did they represent? Certainly not Tanjong Pagar as their stadium wasn’t there. They rented in Queenstown.

Same elsewhere. Geylang rent a stadium in Bedok. Balestier rent a place in Toa Payoh. Now Singapore isn’t renowned for developing community spirit, but football can be a uniting factor but only as long as you’re representing and present in that community, I’d argue.

Look at the examples where it does work. State teams in Malaysia. Kelantan, Johor, Kedah and Pahang – as four examples – are all able to garner huge support and get good crowds when successful because they represent someone and something tangible. The weakness is that, again, the teams don’t own their own stadiums or budget, so are at the mercy of political whimsy.

Maybe private firms won’t pump money into State teams as they don’t get control, but it remains a mystery to me why a company – if they do get behind football – don’t focus on a geographical location to get local support. To give Felda some credit, I hear that the stadium in Temerloh is close to completion and that will be their “home”. As an aside, I’d wager (if it was allowed) a lot of money that the stadium will have an unnecessary running track around it, which will ensure the spectator experience is a distant one.

Japan’s J-League actually copied what happened in Malaysia, would you believe. They saw the passion behind the State teams, and “persuaded” major companies to put their resources behind a team in different geographical locations.

The instant result was that the coldness to football in Japan pre-J-League warmed somewhat when those companies took their brand names out of the team names, and instead to support a geographical region. As examples, Sumitomo Metal Industries Ltd became Kashima Antlers, Nissan Motors morphed into Yokohama F Marinos, and Yamaha Motor Organisation became Jubiol Iwata.

My theory is that geographic and community identification was as much bedrock of the J-League success as the introduction of the big star names that played in the early seasons.

Now teams from places such as Urawa, Kashiwa and Ozaka, as well as Kashima, Tokyo and Yokohama are known around the region, and each has a strong local support base. There is something tangible about the Japanese League that means communities are represented, and a team can, if successful, suddenly be visible on a National and, increasingly, International stage. Kashiwa were recently involved in a game with the Argentine Champions in a match beamed across the world.

The common ingredient that makes football so popular is that the fortunes of a team genuinely matter to a group of people or a community. It’s what marks football out as different. It really does matter. It has deeply engrained roots in community. Good football clubs represent something or someone.

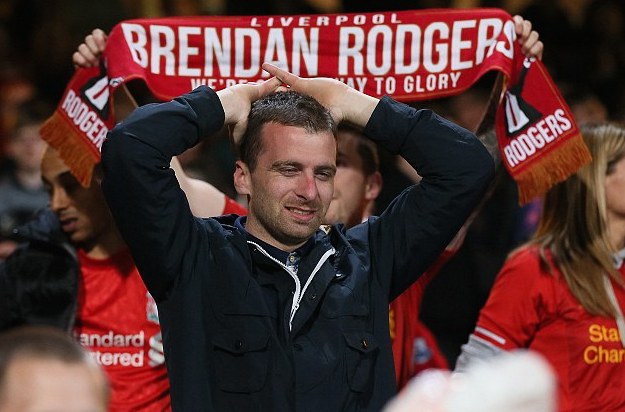

As a child I (sadly) remember bawling my eyes out when Liverpool lost a key game to Everton. It mattered. And I wasn’t the only one, as many of my pals would do the same. (I am still crying these days). I can’t imagine anyone crying because Roger Federer lost a game of tennis. I can’t imagine anyone crying because Tampines lost a game. I can imagine it if Kelantan, Johor or Pahang lost a big match.

The Liverpool’s and Manchester United’s came from the game being played at a community level. The clubs mattered and formed a fan base from where they are from. They mattered in, and to the community. And a community took pride if the club made headlines outside their normal environs.

But the key is that there was a core base of supporters who enjoyed the club. That’s how the great clubs became great. And that’s a part of football in Asia – South East Asia in particular – that has constantly perplexed me.

I ponder why so many obviously successful and clever people don’t see the connection between community / regional identification as being the most essential ingredient of a successful club. If your club matters, then you’re relevant. If you’re relevant, then you’re a real story with gravitas. If you’re a real story, then you become marketable.

Other posts by Dez Corkhill